Chapter V: AGRICULTURE, TESTING EGGS

IT is not necessary for me to stress the importance of agriculture in these difficult times, but if Radiesthesia will help us, as it will, to get a better return for our labours by planting the right thing in the right place, and by using the right fertiliser, so much the better.

The big farmer is in a position to take advantage of the various Government departments which are set up to assist him in the testing of his soil and so on. There are, however, thousands of smallholders and tens of thousands of allotment holders who are not able to take advantage of such facilities and it is for them that Radiesthesia will be found profitable. Time and time again I have heard gardeners say “Broad beans never do well in my garden, I don’t know why, I’m sure.” The answer is, of course, that either the soil is unsuitable or they are using the wrong fertiliser.

Our objective in the following tests is to determine whether harmony exists between plant and soil and, when necessary, between plant and fertiliser. If a plant is not in harmony with the soil in which it has been planted it will grow but it will not thrive. That is common knowledge to us all but, generally speaking, we have to find out for ourselves by trial and error, whereas Radiesthesia will give us the answer in a matter of minutes.

Let us, for example, suppose that you have a small plot of ground in which you decide to grow tobacco, although you do not know whether the soil is suitable or not. If you plant it and it is a success, well and good; if it is not, you have lost the use of the plot for about six months, and have spent time and money to no purpose. The test by Radiesthesia is not a difficult one. As you

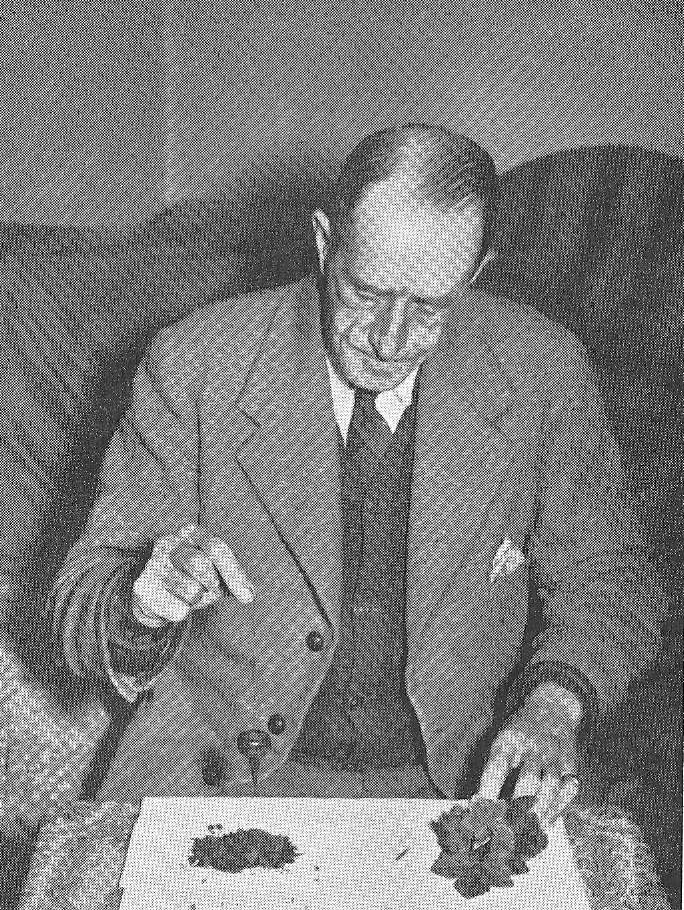

may have several samples on the table at the same time I suggest that a newspaper be spread for the purpose. Take a small sample of soil from the plot, a large handful is sufficient, and place it in a small heap on the paper. About eighteen inches away from the heap of soil, place a tobacco seedling, a leaf or some seeds, but preferably a seedling. Hold your pendulum over the heap of earth and when it is gyrating strongly move it from the soil to above the seedling and watch the result closely. If the gyrations increase then the soil is in harmony with the plant and is therefore quite suitable for growing tobacco and you have nothing more to worry about. If the gyrations decrease it means that the soil is not particularly good although not bad, for the purpose. Should the pendulum change over from gyrations to oscillations it signifies that the soil requires some form of fertiliser to make it suitable. If, however, the pendulum gyrates in the opposite direction, the soil is unsuitable and no attempt to grow tobacco should be made. This test can be applied to anything that grows in the ground — vegetables, flowers or fruit trees and bushes, but a living specimen must be used as a sample. A dead twig or leaf, for example, should not be used.

We will suppose that your pendulum has indicated that the soil requires some form of fertiliser in order to make up some deficiency. In order to make this test you must have small samples, about two ounces, of each of the various fertilisers you have at your disposal. You must now determine which fertiliser is in harmony with the tobacco seedling so the soil sample must be replaced by the samples of fertiliser, placed several inches apart so as to be clear of each other’s field of influence. Hold your pendulum over the tobacco plant and when it is gyrating move it above each of the fertilisers in turn, the one that gives the strongest reaction will be the right one for tobacco growing. You will probably find no difficulty in selecting the right fertiliser because the pendulum will continue most likely to gyrate over one and decrease or stop over the others, but it may take a little practice before you get it right.

Having found which fertiliser is the most suitable, put the others away and bring your samples of soil into use again, as you must now determine how much fertiliser is required for the heap of soil. This is a somewhat delicate test so it is advisable for you to have an assistant. Hold the pendulum over the earth and then move it to the plant and while it is gyrating let your assistant add the fertiliser, a very small quantity at a time, to the heap of soil.

As the fertiliser acts as a tonic the gyrations of the pendulum over the plant will increase up to a point. When you think that point has been reached stop adding the fertiliser. If more is added the gyrations will decrease and you will know that you have added too much. Again a little practice is necessary before you will be able to decide when sufficient fertiliser had been added. Careful measurements will give the exact amount of fertiliser to use, or you can, of cours, take the manufacturer’s figure as correct, but do not lose sight of the fact that too much fertiliser is as bad as too little.

In order to prove what you have just read I suggest that you take a rhododendron leaf and a small quantity of garden lime. Apply your pendulum and you will find that strong discord exists between the two, the pendulum gyrating in the opposite directions. I believe it is common knowledge amongst gardeners that the rhododendron does not thrive in soil with a large lime content, but I did not know this when I made the test so it must have been a true reaction and not our enemy, auto-suggestion. Similarly, some time ago when I was testing various vegetables and flowers, the only harmony I got was between a tomato leaf and a potato leaf. I was pleasantly surprised when I found that they are of the same family.